From Studio Actions to Social Performance: Nguyễn Minh Phước and the Birth of Ryllega Interview and Translation by Đỗ Tường Linh

Article details

Interviewee

Type

Release date

28 January 2026

Journal

Pages

31-39

Đỗ Tường Linh: Could you share a bit about the time when you first began making performance works? Back then you were studying at the Vietnam University of Fine Art (Yết Kiêu) and starting out as a painter. Why the shift?

Nguyễn Minh Phước: Well, it followed the natural course of social development. After Đổi Mới, there was suddenly more access to information. There were books and journals from abroad, and people returning from overseas studies brought back new knowledge. At that time, there was no internet yet. It was mainly foreign books and journals, mostly from Europe and the U.S. They introduced new forms of art that went beyond what was taught in the curriculum at the Vietnam University of Fine Arts.

So it wasn’t just about painting or sculpture anymore, and it wasn’t entirely dependent on material. Instead, there was more emphasis on conceptual art, on the idea and the concept. The approach to art became much more open, which I found very compelling. So, I started experimenting as a way of exploring further. It had many advantages. First, you weren’t so bound by material. Of course, material is still important, but with performance you didn’t need big expenses and you could still convey an idea or an artistic concept.

Second, performance could allow you to interact directly with the audience, something painting or traditional sculpture couldn’t really offer. With painting, the viewer usually has to guess or require an explanation, it’s an approach tends to be academic and sometimes dry. Performance, on the other hand, opened up a new direction—closer, more connective, and contributing to the evolving relationship between art and society. At that time, I simply wanted to experiment, both to understand this medium and to better understand the artistic environment around me.

ĐTL: Could you share when you made your first performance work and describe it for us?

NMP: At first, honestly, I didn’t really understand performance, I hadn’t grasped its concept fully. I just thought it was interesting and tried it out. My first piece was probably around 1998 or 1999, I can’t remember exactly.

I did it right in my studio. I asked Thụy, an artist and colleague, and another friend to film and photograph it. But looking back later, I realized it wasn’t quite in the spirit of performance. It was more interpretive, more like ‘acting’ than ‘performing’, so it didn’t really touch the essence of performance art. Later, when I understood more deeply and practiced more, my approach gradually changed and developed.

ĐTL: When you say “not quite right,” do you mean that was just your own feeling, or because it was criticized?

NMP: Oh, it was entirely my own realization. I did it in the studio, without an audience, so it was really just experimentation, research, a kind of self-study, self-discovery.

Later I learned that there were other artists, like Mr. Shimoda, who often did solo performances to no audience. He said he did them to experience his own emotions, to observe his work himself, without needing an audience. That’s also a valid approach, which I only came to understand later. But at the beginning, I was simply testing whether I felt satisfied, like when you sit and paint alone. It doesn’t necessarily require an audience to count as art.

At the very start, because I didn’t yet understand the essence of performance, my work was still theatrical, a bit overdone, since I worried that others wouldn’t understand or wondered what they might think. So it was still far from the true meaning of performance art. Later, after I read more, I came to understand better: performance isn’t just “doing something strange.” It’s an action, a happening, a chain of experiences using your own body to convey a message. It may involve interaction, spatial installation, communication with viewers, but the core is: What idea are you trying to convey? That message is expressed through action, the body, the space, and the relationship between artist and audience.

Only then did I begin to understand more deeply; before that, it was just instinctive, intuitive. Even now, many people do performance, but I think… they still don’t quite understand its essence. Of course, this is an experimental medium, and a very diverse one, which often blurs the boundaries between genres. So, performance artists are also easily misunderstood.

ĐTL: Could you describe that first work a little? Do we still have any documentation of it?

NMP: I made that piece entirely out of my own emotions and circumstances at the time, as well as my thoughts about society then. It was a very simple work.

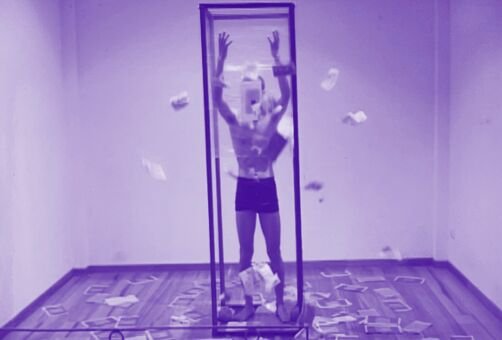

I remember I built a small iron frame, not exactly a cage, more like a rectangular structure, about 2 meters tall and around 80 centimeters wide. I stood inside that frame and bound myself with ropes, wrapping and tying my body. Around me were a lot of joss papers, imitation money for the dead. At that time, my thinking was very simple, very plain. Fresh out of school, just stepping into life, I felt constrained by the pressures of making a living, by responsibilities, by the burdens of daily survival. The act of tying myself up directly expressed that feeling: trapped, tightened by reality.

Back then, I was just a recent graduate, so my thinking was still very straightforward and unadorned. I simply wanted to express my personal condition at that moment, but also hint at something broader: although post-Đổi Mới society had opened up, it placed too much emphasis on the economy, while neglecting other fields like education, healthcare, or cultural and artistic life.

ĐTL: Could you share about the development process in your performance art practice? What major changes have occurred in your approach to performance over the years?

NMP: That was my first work. Later, as I understood more clearly what performance was, I began creating many more works. From the year 2000 onwards, when Nhà Sàn started operating, I had more space to experiment and perform. Other artists also participated. I began making several more pieces, and the more I practiced, the more I understood this medium.

I have scattered works from that period, some of which still have documentation. Some pieces were made during workshops, created spontaneously when inspiration struck. A representative work is Blue, Red, and Yellow. This piece marked a shift in my approach to performance: I no longer used my own body directly, but began using the bodies of others, and even animals.

For example, in a performance at the Goethe-Institut, I included a chicken as part of the work. I realized that I didn’t need to be limited by material or even appear on stage myself. Performance only requires a movement; a body, be it human or animal; and a clear idea. The artist doesn’t have to perform personally, but can direct a situation or action to become art.

Later, I learned that many artists worldwide were also working in this way. When I went to the U.S. in 2005 to screen my work and participate in an artist talk, one artist asked if I knew of a very famous performer, Vanessa Beecroft, who hires models for her performances. She often arranges models like mannequins in museum spaces. I didn’t know her work at that time, but when I inquired further, I learned that the piece she referred to was created after my work (Blue, Red, and Yellow in 2003; hers around 2004).

That fascinated me: even without knowing each other, artists in different parts of the world can follow similar directions in their practice. They are no longer just ‘performers’, but ‘directors’ of their performance pieces. And that, in itself, is still considered performance.

ĐTL: Could you revisit the work Sleep Walking – Mộng du from that year? Why did you start performing with a whole group of people instead of just using your own body, as you did initially?

NMP: Initially, I planned to make a documentary about people migrating from the suburbs into the city. At that time, the economic gap between urban and rural areas was very large. Many people came from the outskirts to live on the sidewalks, doing jobs like porters, shoe-shiners, street vendors, even sex workers, laborers… They were treated as “urban trash,” often rounded up by authorities and sent back to their hometowns.

I asked myself: Why must they leave their homes and villages to live in the city, being looked down upon and trampled like this? They have families, dreams, and aspirations like anyone else. Many were veterans but lacked the skills or education for better work. Life in the countryside was poor and economically stagnant. They sacrificed themselves for happiness, for their children’s education, for the hope of a better life.

While making the film and interacting with them, I realized they were just ordinary people, with their own dreams and desires. They lived quietly, repeatedly taken by the police, sometimes tricked into returning to their villages, only to escape back to the city to continue living.

From that, the idea emerged: Why not use these people in a performance?

At first, I thought about creating a work combining video, performance, and installation, because contemporary art was no longer limited to a fixed material. It is the idea and emotion that define art. The work became a synthesis of video, performance, and happening, making it hard to categorize. Viewers interacted very genuinely with the performers. The laborers and porters shared their dreams and lives, writing their wishes on the walls. However, the work faced challenges with censorship due to its democratic nature and the fact that participants could voice their own perspectives. The performers feared getting caught again, so convincing them to participate proved difficult. In the end, the Goethe-Institut provided funding of about 1.6 million VND to pay 16 participants, essentially as a one-evening labor fee.

The work was quite successful; many visitors cried when hearing and reading their stories and dreams. I managed to preserve some videos and key images from the project, though some documentation was lost. Later, I was invited to the U.S. to do a similar project for disadvantaged Mexican communities. But I declined, both because of time constraints and because I wanted to work with communities I understood more deeply.

Other invitations came from Europe, like a project for the Vietnamese diaspora in Germany, but I wasn’t interested in repeating the same motif too many times. I need passion to create meaningful work; without it, the work would lack depth. So I continued developing one or two more versions of the piece. Eventually, however, I no longer felt the same excitement. Not a total loss of interest, but I felt that doing performance in that way was still not enough, and I wanted to try something else. Since. then, I haven’t returned to performance art.

ĐTL: So the first version of Sleep Walking was in 2003 at the Goethe-Institut Hanoi, and the subsequent versions in 2004 and 2006 were at Ryllega, the art space you co-founded. Were the participants in these versions similar or different?

NMP: They were different. These were not pre-selected people. They were wanderers, transient in a sense. Each time I did the work, I had to… find the right participants all over again. There used to be many people fitting this profile, but later, as authorities began the crackdowns, it became much harder to find them. It wasn’t as simple as before; you couldn’t just go out on the street and have dozens of people gather around instantly. Eventually, I had to go to more remote areas to find people like that.

ĐTL: So you paid them, like a day’s labor, but instead of doing manual work elsewhere, they spent their time participating in your art project, correct?

NMP: Exactly. They entered an art space, and together we created the work. When the audience came, it was usually just for one session, so they could interact directly, ask questions, raise issues, and participate in many spontaneous moments—the happening itself. My role was mainly to observe, research, and think about how to develop the piece further, or explore other approaches. That was my working method. Later, when I felt the project had fully evolved, I stopped after the third version, which was Circle at Ryllega.

ĐTL: Could you share a bit about Ryllega? Why did you open this space back then, and why did you do it with Thụy? Could you also explain the meaning of the name and the artist-run space model you operated?

NMP: At that time in Hanoi, there were very few spaces for contemporary art or new forms of art beyond painting and sculpture. There were plenty of galleries, but most existed to sell paintings, sculptures, or souvenirs to international visitors, not as genuine art practice spaces. Underground artists had very limited options, mostly working in embassies or foreign cultural centers like L’espace or the Goethe-Institut. British Council had very little art programming then, focusing mainly on language education.

There were also some small artist-run initiatives, like exhibitions in private studios or open spaces—for example, Salon Natasha organized by Ms. Natasha, or Đào Anh Khánh’s private space in the late 1990s. Nhà Sàn was an official space founded by Lương and Đức for practicing artists, where I created my first installation work, Go West, featuring hands emerging from the ground.

At the end of 2002 and beginning of 2003, I found a rental shop at 1A Tràng Tiền, a prime location at a good price, and thought, Why not use this space to bring contemporary art to a wider audience? Previously, exhibitions were mostly in embassies or cultural centers, reaching very few viewers, mainly other artists and acquaintances, not the general public. Contemporary art was still a new concept, and many people didn’t understand what performance or curatorship meant. Even the word ‘curator’ was controversial. Although it was risky and bold, I was determined to do it and received support from other artists and some cultural funds.

I invited Thụy to collaborate from the start. He thought simply, “You do it, and I’ll help by co-investing in the renovations.” The name Ryllega is a bit funny. In Vietnam, galleries were managed by the Ministry of Commerce, not the Ministry of Culture, so they were considered purely business ventures. I thought, why not use this commercial model to restore the gallery to its proper function: connecting artists and audiences, presenting new works, and bringing authentic art closer to the public.

Mr. Lương suggested the name Ryllega because it resembles relegar in legal terms, carrying a slight political nuance, and I thought it was a good name. I checked online and it wasn’t already in use, so I decided to keep it. The name also symbolizes turning a ‘wrong’ model of gallery in Vietnam into a ‘correct’ one, essentially doing the opposite of what others were doing. That’s the story of Ryllega.

ĐTL: As you mentioned earlier, Ryllega was right in the center of Hoàn Kiếm District, next to the Hanoi Opera House, a prime location. Did you need permits for your events, performances, or exhibitions, or were you completely free to organize them? Could you share how you negotiated with the local authorities?

NMP: No, I never applied for permits. Here was the situation at the time. First, I opposed the idea of needing a permit for art because the officials reviewing it often had no understanding of it. Having to explain your work to someone who doesn’t understand art, just to get permission, felt very unfair. It was better not to do it at all. I accepted the risk: We just did it, and if it were to get banned, then so be it.

I also told the participating artists that working at Ryllega meant accepting that the space could be shut down on opening day. Only those willing to take that risk could participate.

There was another situation. Some international artists came through diplomatic channels and wanted to collaborate with us. For example, Ms. Allay Cistre was sent by the U.S. State Department as part of a Vietnam-U.S. cultural exchange. She initially wanted to work with the University of Fine Arts but faced difficulties, so she came to me. For bigger programs, we would collaborate with Nhà Sàn, which had few events at the time. She was responsible for permits. The diplomatic route made it very easy. A formal note would be enough, no permit was needed. We benefited from international support that way.

ĐTL: And the great thing is, right next to Ryllega there was a street-side tea lady, so even the gallery’s ordinary receptions allowed people outside the art world to encounter art.

NMP: Exactly. That was part of making art accessible to society. You have to consider the history of Vietnamese culture: so many years of war, followed by limited access to information. Fortunately, now people can freely use the internet, and Vietnam has progressed quickly. Vietnamese people are not slow learners. Knowledge, social awareness, and an understanding of art and culture developed rapidly thanks to the internet.

At that time, cultural knowledge, both of our own traditions and other cultures, was very limited. The more society could be exposed to art, the better. For example, some artworks might be confusing at first, like when people saw something on the street and didn’t understand it. That curiosity is exactly what sparked engagement. I would even ask the artist to explain the work to each viewer, even to a child asking questions. That benefits everyone—the art, the artist, and society as a whole.

Of course, many people might not fully understand and just respond with “uh-huh” or “oh, okay.” But even that initial reaction stays with them. Later, when they encounter something similar, they’ll recall the artwork and think about it again. This is an easy way to gradually influence people’s thinking, their understanding of beauty, goodness, and truth—not just in art, but in the philosophy of life. The goal is simply to make society better. Essentially, art exists to bring people happiness and joy.

Back then, the street-side vendors around Hoàn Kiếm Lake were all closely watched by the police. We had to be careful, but I didn’t worry too much. I let people, like the tea lady, sit where they wanted, watch, or do whatever they liked. All of them were very fond of me. One time, a sex worker was chased by the police and ran into the gallery, saying, “Can I just stand here for a bit?” I told her, “Sure, just stand wherever you want.” Another sex worker even stored a pile of condoms by the window. I joked, “Why are you putting this here? Won’t it make the whole house unclean?” She said, “Just for now, if someone wants to use it, they will use it—we all have to be careful.”

Over time, I grew to appreciate all of them. Even the police who patrolled around became helpful in their own way. If anyone suspicious appeared, or tried to loiter or steal, the tea lady or others would warn me immediately. Nothing ever got stolen from Ryllega. I realized that living honestly and staying close to people was a good thing. Of course, there were some downsides, but the benefits outweighed them. I could live more freely, without constantly defending myself, which was quite enjoyable.

Keep Reading

Vừng ơi! Mở ra Sesame, open!

“Sesame, open!”—a phrase from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves —has always meant more than just opening a door. It’s about discovering something hidden, something precious. It was used as...

Trần Lương interviewed by Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy

Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy: Performance wasn’t your starting point, yet it plays an important role in your practice. How did that journey begin? Trần Lương: In the very beginning, getting into contemporary...

The Ending of a Performance

In March 2023, I performed Matxa VIP at the Art Patronage & Development (APD) in Hanoi. It was the culmination of one and a half days of workshops on performance...

An index to The Appendix

The Appendix a tube-shaped sac attached to and opening into the lower end of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals. a section or table of additional matter...