Memory is Air

Article details

Contributor

Type

Release date

28 January 2026

Journal

Pages

24-30

Torment and Experimentation (Lô Lô, 2003)

I lock myself in a black bag

The whole world cannot see me

Seeking the feeling when my breath breaks and no one knows

The black bag is full, breath taut and rigid

When it bursts, what scent will escape?

I lock myself in a white bag

The whole world sees the veins on my face

Seeking the feeling of being pitied in death

The white bag is full of blurred sweat

When it bursts, what scent will escape?

Rain falls on the white bag

Rain falls on the black bag

Is there a difference?

Shh!

Silence!

Plug your ears to listen

Pinch your nose to smell

Close your eyes to see

Very different!

Encountering Ly Hoàng Ly’s “Hành xác và thử nghiệm” for the first time in 2003 through her Lô Lô poetry collection was a revelation. The poem immediately struck me not only for its intensely personal voice but also for its radical, sensorial exploration of the female body. In a post-Đổi Mới Vietnam, where artistic expression was beginning to stretch beyond conventional boundaries, Ly Hoàng Ly’s work embodied a freshness and boldness that opened new ways of thinking about poetry, performance, and embodiment.

The poem’s structure—a repetition of confinement and sensory immersion in black and white bags—creates an intimate, almost claustrophobic tension. The black bag, suffocating and opaque, embodies isolation and the hidden dimensions of the self: a desire to experience the fragility of breath and mortality unseen. The white bag, in contrast, exposes the body to the world, rendering veins visible, invoking both vulnerability and a complex entanglement of pity and gaze. Ly’s exploration of these extremes—concealment versus exposure—illustrates the body as a site of experimentation and reflection, where physical sensation and emotional intensity intersect.

The final stanza, with the rain falling on both bags and the invitation to block sensory perception radically challenges conventional perception: “plug your ears to listen / pinch your nose to smell / close your eyes to see”. It foregrounds subjectivity and embodied experience over narrative or logic, suggesting that the meaning of sensation and difference can only be accessed through immersion rather than mediation.

For me, reading this poem was transformative. It marked my first encounter with a form of poetry that was unapologetically personal and intensely bodily, opening a pathway to contemporary art practices where the body itself could become a site of exploration and performance. It illustrated the freedom emerging in Vietnam’s post-Đổi Mới artistic landscape, where disciplinary boundaries—between poetry, performance, and visual art—could be interrogated and dissolved. Ly Hoàng Ly’s work was not merely to be read but to be felt, sensed, and even lived through, and it revealed the possibilities of art as both a deeply personal and experimental endeavor.

2.

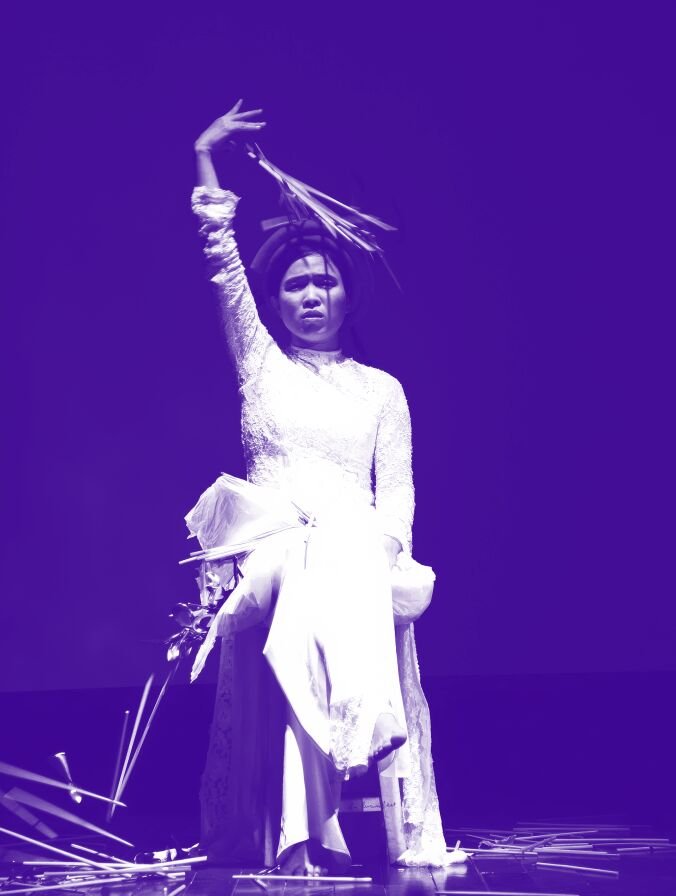

“The Woman and the Old House”, penned in 2001 and gathered into Lô Lô (2003), unfolds like a palimpsest of Hanoi itself—where tradition lingers in crumbling walls, and modernity seeps through the rain-stained windows. When Ly Hoàng Ly steps into the room in her white áo dài traditional Vietnamese dress at Cha và con và thơ (2008, Alliance Française), the poem no longer rests on paper; it rises, breathes, inhabits space. Her body becomes a vessel, a hinge between past and present, a rhythm of memory and decay, a site where history bends and the city exhales its layered, spectral streets. Here, the corporeal and the architectural collide, the temporal unravels, and poetry spills into performance, dissolving boundaries between the observer and the witnessed, word and gesture, self and space. From the opening lines, the old house embodies the weight of tradition and the residues of time:

“Chairs with carved backs, velvet upholstery tattered to shreds.

The fireplace, cold for years.

White marble, crusted black.”

The detailed materiality of the interior—the tattered velvet, cold fireplace, blackened marble—signals both decay and endurance. The house is a repository of history, the physical traces of generations and rituals now in decline. The luxurious craftsmanship of carved chairs and marble surfaces, once symbols of refinement and social order, is juxtaposed with their current state of neglect. In this sense, the house metaphorically represents tradition: culturally rich yet challenged by the pressures of time and modern transformation. The figure of the woman in white áo dài acts as the interlocutor between past and present, tradition and change:

“A woman in a white áo dài sits, legs crossed,

On the only intact velvet chair.”

Her poised, meditative posture amidst the decay indicates resilience, a conscious preservation of self and cultural identity in the face of societal and historical erosion. The repetition of this image throughout the poem emphasizes her role as a stabilizing force, bridging the old and the new. The áo dài itself, a traditional garment, functions symbolically: it is at once a marker of Vietnamese identity and a medium through which the female body negotiates the pressures of modernity.

"The window opens to a rainstorm breaking the amniotic sac of the night sky.

Rust flaking from the iron bars."

The storm, violent and primal, contrasts with the measured stillness of the woman. It represents external forces of change—modernity, urban development, and social flux—that penetrate the protective boundaries of traditional spaces. The flaking rust and damp decay of walls evoke entropy, underscoring the fragility of cultural and historical continuity in the modern era.

Ly Hoàng Ly’s attention to microscopic, almost imperceptible details, such as bacteria clinging to dust or cockroaches stirring under floorboards, reveals a profoundly sensitive and distinctive approach to depicting place and urban memory.

“Bacteria cling to each grain of dust,

Eavesdropping on the growth of mold.

Under the water-gleaming plank bed, like a mirror,

Is the night of the last century,”

The poet transforms the minute and often overlooked elements of the domestic interior into carriers of history and affect. Bacteria and dust, typically associated with decay or neglect, are anthropomorphized as witnesses (“eavesdropping”) suggesting that even the smallest components of a space participate in the accumulation of memory. By doing so, Ly Hoàng Ly renders the house—and by extension, the city of Hanoi—as a living, sensitive entity, capable of holding the layered temporalities of the past.

This micro-level attentiveness demonstrates a sensitivity that is both literary and phenomenological: Ly Hoàng Ly invites readers to inhabit the space fully, to perceive it not just visually but sensorially, as a body inhabits and experiences the urban and domestic environment. This approach distinguishes her work from more conventional urban or domestic descriptions, where the focus might lie on surface aesthetics or social narrative. In her prose, even the tiniest agents are imbued with significance, making the city itself a living, dynamic character.

These lines suggest that modernity is not only external but seeps inward, manifesting in the slow, almost invisible processes that erode tradition from within. Yet the woman’s continued presence anchors continuity and resistance, such as here: “Keeping her unborn child steady and defiant”. The unborn child may be read literally, signaling pregnancy, yet metaphorically it embodies potential, vulnerability, and the future, positioned between societal expectations, cultural memory, and personal agency. The juxtaposition of the woman’s white áo dài—a traditional symbol of purity, sometimes associated with virginity—with pregnancy introduces tension: it challenges social taboos, destabilizes norms, and places her body at the intersection of sacredness and transgression.

The poem’s haunting refrain, “Oe oe oe”, resists definitive interpretation. It could be the cry of the unborn child, as it anticipates birth into a turbulent, decaying world. It could also be the woman’s own lament, a manifestation of exhaustion, grief, or defiance. The ambiguity of sound collapses temporal and bodily boundaries, linking maternal and fetal experience, interior and exterior worlds, tradition and modernity. The climactic emergence of the child, also in a white áo dài, embodies reconciliation and continuity:

“A little girl in a white áo dài slips gently down from the last intact velvet chair.

Her round eyes, clear as glass.

She walks a bewildered circle,

Touches the fireplace, the window, the walls, and all the damp decay.”

The child’s tactile engagement with the decaying house enacts a negotiation between past and present, tradition and change. The white áo dài, again, carries dual meanings of purity and inherited identity, now embodied in the next generation. Tradition is neither static nor ossified; it is activated, negotiated, and reinterpreted through bodies, gestures, and generational continuity.

The poem closes with a gesture of cleansing and renewal.

“Raindrop-like sunlight falls endlessly,

Washing her dusty hands clean.”

Rain and sunlight intermingle, suggesting the dialectic of destructive and regenerative forces. History, corporeality, and memory converge in a luminous moment of hope, leaving the reader with a vision of continuity and transformation, where tradition and modernity coexist in tension, and the body becomes a site of both inheritance and experimentation.

3.

From . To . Having (No) Beginning And (Having) No End

(written for a series of performances at Nhà Sàn Collective, July 2015)

One can control the starting point

But cannot control the destination.

A party cannot exist without people,

Yet a party might exist without a single soul.

Food is laid out for flies,

Or there is no food, and thus, no flies.

From A to B is a party where the starting point is controlled.

Starting points A, A’, A’’, A’’’, A’’’’, A’’’’’ and A with infinitely more apostrophes

cannot be counted aloud within the span of a human life.

The starting point is connected to another resting point.

The bell tolls at noon.

The starting points begin to roll and stop at the same place.

The marker is 6 PM.

Fated to meet,

But will they even see each other?

A resting point is not a destination.

Seeing each other, tracking one another—this doesn’t mean we understand what on earth anyone is truly doing.

Not seeing each other, not tracking one another,

Letting others observe all of us from afar.

Meanwhile, we just keep living, keep rolling, keep live-streaming our existence.

The feast might only exist online,

Food listed on the tangible table is sniffed by the online crowd,

like offerings prepared for the spirits of the departed.

The departed rise from the screens,

Swirling online, haunting the living world.

(Translated from Vietnamese by Ly Hoàng Ly)

One can control the starting point.

One cannot control the destination.

A.

A’.

A’’.

A’’’.

A’’’’.

A’’’’’.

A with infinitely more apostrophes.

Time spills.

Rolls.

Waits.

Cannot be counted.

Not in a human life.

Not in one breath.

The bell tolls at noon.

Markers.

Anchors.

Six PM.

Fated to meet.

Or pass unseen.

Observation is not understanding.

Seeing is not knowing.

We live.

We roll.

We stream ourselves into the world.

Food on the table.

Or not.

Flies.

No flies.

The feast exists online.

Or in memory.

Or in the watching of ghosts.

Departed rise,

swirling through screens,

haunting the living.

Duration is subtle.

Quiet.

Patient.

The woman is still.

The body as instrument,

medium,

vessel of time.

Gestures accumulate.

Moments fold into one another.

Infinite apostrophes of now.

The white áo dài returns.

A woman sits.

Crossed legs.

Stillness.

Rain.

Decay.

Cockroaches stir.

Dust breathes.

An unborn child

steady.

Defiant.

Time held in a body.

The silent measure of history.

The pulse of waiting.

Oe oe oe.

Who cries?

The unborn?

The woman?

Time itself?

A child emerges.

White áo dài again.

Round eyes.

Glass-clear.

Touching walls, fireplace, decay.

Exploring the folds of history.

Tradition is not fixed.

Modernity is not destruction.

Movement activates meaning.

The past is embodied.

The future is lived.

Raindrop-like sunlight falls.

Hands washed clean.

Time cleanses.

History, body, memory converge.

A luminous now.

Ly Hoàng Ly: female performance artist in

Time is her medium.

Subtlety her tool.

Presence her gesture.

Duration her canvas.

From beginning.

To no end.

The poem rolls.

The performance unfolds.

Moments multiply.

Gestures accumulate.

Time is not linear.

Time is lived.

Time is felt.

Ly Hoàng Ly & Đỗ Tường Linh

*“Memory is air” is a line from “Memory Memory (Ký ức)”, published in the first issue of Văn nghệ new edition in June 2021. This translation was made by Ly Hoàng Ly and Việt Lê. The text was also used in Ly Hoàng Ly’s performance.

Keep Reading

From Studio Actions to Social Performance: Nguyễn Minh Phước and the Birth of Ryllega Interview and Translation by Đỗ Tường Linh

Đỗ Tường Linh: Could you share a bit about the time when you first began making performance works? Back then you were studying at the Vietnam University of Fine Art...

Vừng ơi! Mở ra Sesame, open!

“Sesame, open!”—a phrase from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves —has always meant more than just opening a door. It’s about discovering something hidden, something precious. It was used as...

Trần Lương interviewed by Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy

Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy: Performance wasn’t your starting point, yet it plays an important role in your practice. How did that journey begin? Trần Lương: In the very beginning, getting into contemporary...

The Ending of a Performance

In March 2023, I performed Matxa VIP at the Art Patronage & Development (APD) in Hanoi. It was the culmination of one and a half days of workshops on performance...