A Direct Punch in the Face and Ears: The Porno-Sadistic Force of Đại Lâm Linh

Article details

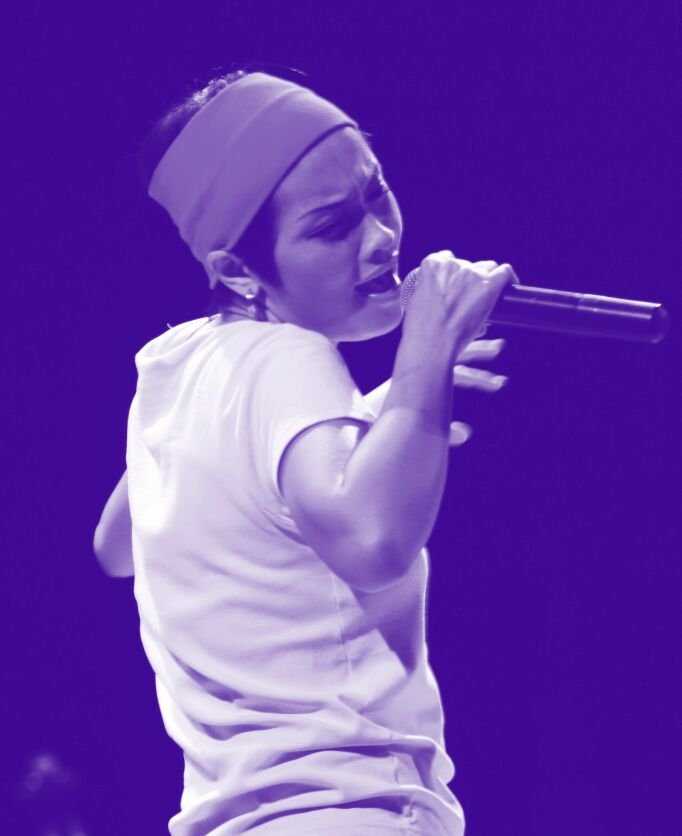

Two female singers. One rocked a shaved head. Her punk appearance contrasted with the other singer’s seductive femininity. Both were draped in black dresses. Wrapped in theatrical fog. Backed by a full band behind, together unleashing a dark, dissonant soundscape. Harsh electronic sonic motifs, punctured by seemingly endless screaming and relentless chanting. Possessed by the guttural depth of pain, terror, pleasure, sadness, and madness that do not belong to the living world. Peppered with the uncanny familiarity of Vietnamese folk instrumentation and melodies. But this sweet, melancholic hint was drowned out by the visceral intensity of the vocal performance and the extreme affects of the singers. Two women losing themselves on stage. Live. On Vietnamese national television.

Like most people in Vietnam, I encountered Đại Lâm Linh in 2010 through Bài Hát Việt [Songs of Vietnam], a State-run competition highlighting Vietnamese composers and singers of popular music. Đại Lâm Linh is a band and a short-lived musical project comprised of three members—Ngọc Đại, Thanh Lâm, and Linh Dung—who came together in 2007 and performed mainly for the small audience that exists for contemporary music and art in Vietnam. In contrast, the appearance on Bài Hát Việt was broadcast widely on VTV3, a State-owned television channel dedicated to entertainment for the masses. Đại Lâm Linh’s eccentric performance felt completely out of place and became an immediate national phenomenon. The flashes of memory offered above cannot do justice to how much of a shock the performance was to my psyche as a high schooler, who had little interest in the arts. I remember spending the following weeks laughing with my friends about the performance, participating in the social media craze around it, consuming countless articles that emerged out of it, rewatching low-quality YouTube recordings of it, obsessively trying to make sense of what it was that I had seen. To dismiss it. To stabilize the turbulence induced in my senses. To contain the aesthetic rupture, whose excess bled out from underneath. If such a constellation of sounds could exist and even constitute music, who knew what else could be possible?

This what-else-ness of the aesthetic dimension, felt as a psychic attack on the constitution of myself and, by extension, the larger social order, explains the magnitude of the extremely vile responses that flooded in from the press as well as the general public. Referring to Đại Lâm Linh as “the three monsters” [tam quái], VTC News described the performance as “rebellious, haunting, and even arousing.” Giáo Dục Việt Nam, an online press dedicated to education, called their music a “direct punch to the audience’s face and ears.” The most-viewed YouTube video of Đại Lâm Linh’s Bài Hát Việt performance is of Cây Nữ Tu, which came with a subtitle from user AndyTao7: “Ecstasy with Acoustic or Musical Rape” (Phê Cùng Acoustic hay Hấp Diêm Âm Nhạc). I remember this kind of vulgar and offensive language was littered all over the Internet and social media at the time, unleashing a public tidal wave of exaggerated defenses against the threatening otherness of Đại Lâm Linh’s musical performance.

For Barley Norton, a British ethnomusicologist researching Vietnamese folk music and a filmmaker of the documentary, Hanoi Eclipse: The Music of Dai Lam Linh (2010), the otherness of Đại Lâm Linh’s music is evident in the way it is labelled “experimental” music by the Vietnamese press. This has little to do with the history of musical experimentation as understood in the West; rather, “experimental” here functions as a “marker of alterity,” a codeword for a kind of un-Vietnameseness, an unwanted consequence of Westernization. Yet, the band’s music follows many of the same Western pop conventions that have long shaped Vietnamese popular music: song structures with clear introductions and resolutions driven by tonal chord progressions, and melodies carried by repeatable poetic refrains. What makes Đại Lâm Linh startling is not the adoption of these forms but their destabilization, pushing recognizable structures to the edge of coherence. In doing so, their work exposes the contradictions of a modern Vietnamese identity itself, making the music’s disturbance not just aesthetic but social.

Fast forward 15 years, Đại Lâm Linh remains a small blip of virality in the Vietnamese public consciousness. The band only recorded one album together and they never returned to the national spotlight. But to me, witnessing them on national television felt like an initiation ceremony, even though its performative effects of inducting me into the world of artistic experimentation did not actualize until several years later when I stumbled upon and eventually studied Western avant-garde performance. In the meantime, the residue of Đại Lâm Linh’s music lay more or less dormant, quietly haunting me, instilling an internal compass that pulled me away from, to borrow Georges Bataille’s phrasing, the “habitual homogeneity” of the ordinary. The Bataillean excess of Đại Lâm Linh—the violent rupture of predetermined forms to edge towards the obscenity of formlessness—was first registered as a sonic assault and a sadistic violation, whose ruthless intensity demanded resistance. I held that resistance for as long as I could, but the simmering cruelty of the music was quiet and relentless: it crept in, cracked me open, and unraveled thread by thread the psychic defensive structures that I had woven together to contain the aesthetic experience. In the end, the sadism I once resisted became the very force that unmade and remade me, turning aesthetic violence into a strange kind of wounding that induced curiosity, anxiety, confusion, overwhelm, and pleasure all at once.

“Exigent sadism,” a concept developed by psychoanalyst Avgi Saketopoulou, fleshes out the psychic need for risk-taking, for wound-touching, for coming undone, for relinquishing control, for surrendering to an interpersonal experience that hovers at the edge of violations. This sadistic process may result in harm and/or it may produce radical transformation. There is no guarantee, only the necessity to take a leap of faith. Saketopoulou’s notion of exigent sadism shuttles underneath the binary of “sensible sadism” (restrained, reasoned, regulated) and “destructive sadism” (limitless, annihilating, with no regard for the Other). Instead, it names a terrifying, aggressive, and imaginative force that is driven by an ethical necessity of wounding, undergirded by a kind of “odd care.” The exigent sadist inflicts violence not (just) because they want to hurt others, but because they believe they have to.

In this sense, Đại Lâm Linh’s music does not seek to wound its listeners, though it is often received as such. Their intensity arises not from antagonism but from a negotiation both within and against the limits of musical form until those limits begin to rupture. The blow is felt not because they aim to strike, but because the structures themselves start to split open. If their music seems to punch its listeners directly in the faces and ears, it does so out of a fierce, unruly conviction that something of the status quo must be shaken loose. Their sonic violence inflicts pain while also carrying a strange allure and seduction, demanding the listeners to linger with the discomfort, survive the disorientation, and, should they surrender to it, emerge changed.

If one has the opportunity to interact with Đại, the band’s composer and spiritual core, this framework of exigent sadism feels far from abstract. Animated and wildly expressive, Đại moves through the world with a raw, unfiltered intensity, flashing between affection and aggression, irreverence and provocation. His speech is peppered with obscenities; his presence charges every encounter with an unpredictable energy. He is known by the nickname Đại điên (crazy Đại), partly due to the types of music he pursues, partly for his emotional volatility and his reputation of being difficult to work with. To witness him speaking is to be thrown off balance, to feel both thrilled and threatened. For instance, he recounts to me a story of learning to throw knives to intimidate the cultural police, who came to his house during the censorship crackdown following the self-release of Thằng Mõ 1 (2013)—all the while locking eyes with me, sending a cold jolt down my spine.

His dominating, emphatic, and quasi-drunken style of storytelling reminds me of my father. There is something deeply frightening about many northern Vietnamese men of that generation who went to war, all of whom seem to carry an urgent compulsion to narrate and transmit their stories to any available pair of listening ears. Their tales are drenched in unspeakable intensity, rendered through a kind of exaggerated theatricality that feels, at times, magnetic but more often alienating. There is little space for me to enter, because the space they inhabit is unimaginable. There is hardly a conversation to be had; listening to them feels less like dialogue and more like stepping into a temple of a faith I do not practice, where I am only ever a silent observer.

***

Đại composes the song Chiều [Evening] in honor of his fellow soldiers who died in Quảng Trị, a site of some of the most brutal fightings in the Vietnam War in 1972. Anchored by sparse, dissonant piano chords and low, steady percussion, Chiều unfolds with a mournful restraint. Its sorrowful zither lines drift through the arrangement, while Lâm and Linh’s vocals remain unusually subdued. It stands as one of the softer pieces in the entire project. Its vivid yet abstract imagery comes from original lyrics written by poet Nguyễn Trọng Tạo, conjuring a world soaked in the soft twilight-gold of the evening.

Vàng da, vàng tóc, vàng chiều

Chiều rơi rơi…

Vàng cây, vàng đá, vàng ta, vàng người

Chiều rơi rơi…

Yellowing skin, yellowing hair, yellowing evening

Evening falls…

Yellowing trees, yellowing rocks, yellowing self, yellowing people

Evening falls…

Nguyễn Trọng Tạo never mentions war directly. Yet the poem vibrates with a quiet awareness of impermanence, steeped in the melancholy of dusk—the fragile passage between light and its vanishing. In the last line of the full poem, Thời gian nghe tím một trời phù dung [Listening to time purpling the sky with confederate roses], Nguyễn Trọng Tạo juxtaposes this golden twilight threshold with the ethereal purple of the confederate rose, a flower that blooms in the morning and wilts by night. It becomes a haunting metaphor for fleeting life, for beauty touched by death. Đại borrows this melancholic twilight landscape and fuses it with the memory of Quảng Trị, letting the quiet horror of his survival seep into the song. While a listener might not immediately register the song as a meditation on war, the presence of death feels markedly different from the poem—less symbolic, more specific, and sharply painful. Part of the song’s specificity comes from the heavy incorporation of Hò Huế, a folk singing tradition associated with the city of Huế and central Vietnam, thus evoking the geographic proximity of Quảng Trị. The drawn-out, sweeping melodies of Hò Huế bleed into the aching vocalizations of Lâm and Linh, imbuing the poetic landscape with a visceral tug. Chiều, chiều, chiều, chiều, chiều, chiều… The word is repeated to the point of rupture, unraveling into manic laughter and desperate cries. The content of the lyrics dissolves as Lâm and Linh’s voices hover at the threshold of articulation and abandonment, where language falters and sound becomes a vessel for unspeakable emotions to break through.

What haunts me the most about the song Chiều and, more broadly, what gives the Đại Lâm Linh its devastating punching force is the unruliness of the female voice, specifically the way Lâm and Linh vocalize at what I would call the pornographic register of representation. By pornographic, I do not necessarily mean that they sing about sex, even though they certainly do—many of the lyrics throughout the project are drawn from Vi Thuy Linh’s boldly erotic poetry, which have gotten Đại in trouble with the cultural authority in the past when working on Nhật Thực (2003) with the singer Trần Thu Hà. Rather, what is so pornographic about their voices lies in a kind of too-much-ness, a sonic excess that provokes similarly excessive, almost involuntary responses from the listener. There is a choreographic dimension to their singing that, not unlike pornography, moves the body, compels it into affective motion. The voice does not simply express or communicate; it agitates and arouses. This is where the charge of obscenity lies: not in content alone, but in the raw, embodied force of its delivery, which then interpellates other bodies, drawing them into their own yet-to-be-explored currents of sensation and sexuality.

Their moans raise goosebumps. Their belts resonate with a force of horror. Their nasally wails yank at the heart. Their screams weaken the knees. Their eerie vocal fry prickles the skin. The cracks in their voice tear into the guts—sudden, violent, almost wounding. At times, they articulate with crystalline clarity. At others, they speak in tongues, getting lost in relentless Buddhist chants or dissolving into ecstatic murmurs, erotic gasps, guttural cries. The vocal performance feels heavily driven by improvisation, as if the voice is not delivering lyrical content so much as being seized by it, possessed by a force that exceeds the body and its bounds. Like pornography, their vocal delivery provokes an existential anxiety around the osmosis between the real and the represented: are they simulating, or are they actually submerged in the depth of pain, pleasure, and madness? Hovering at the threshold of the pornographic register, Đại Lâm Linh stages a kind of unbearable, sexually-charged intensity—an intensity they portray, embody, channel, and transmit all at once. There is no safe distance, no shielded position from which to listen. In a true exigent sadistic fashion, their voices do not invite contemplation. They assault, seduce, and ensnare. The raw vocal matter grips my body, demands a response, and refuses to let go.

It is worth noting that the project employs exclusively female voices: besides Lâm and Linh, the melodies of Hò Huế and Ca Trù, a northern Vietnamese chamber music tradition, which can be heard across several songs, are all sung by women (Hạ Vi and Thúy Hà, respectively). Taken together with the pornographic dimension of Lâm and Linh’s voices, I am reminded of Porn Studies scholar Linda Williams’s incisive analysis of female pleasure’s otherness vis-à-vis the money shot fetish in pornographic cinema. Adopting a Foucauldian framework of examining heterosexual pornography as a discursive machine attempting to capture, produce, and proliferate the hard-core “truth” of female sexuality, Williams explicates the paradox of this endeavor: how the obsessive quest to “know” the female pleasure ultimately circle back around to the male cumshot, thus revealing “a lack of relation to the other, a lack of ability to imagine a relation to the other in anything but the phallic terms of self.”

By contrast, Đại Lâm Linh engages a different kind of pornographic register, one grounded not in visual climax or narrative closure but in sonic excess. Instead of displacing the fundamental lack of the phallus through the spectacle of itself, their music dwells in this lack, unabashedly mobilizing the otherness of the feminine and pushing the transgressive force of the female voice to its limits. The unorthodox and extreme vocalizations of moaning, weeping, screaming, chanting refuse resolution. They rupture the very possibility of being captured, and transform the auditory space into one of relentless affect, where the unknowable feminine resounds without grasp—endlessly deferred, forever haunted.

Keep Reading

Memory is Air

Torment and Experimentation ( Lô Lô, 2003) I lock myself in a black bag The whole world cannot see me Seeking the feeling when my breath breaks and no one...

From Studio Actions to Social Performance: Nguyễn Minh Phước and the Birth of Ryllega Interview and Translation by Đỗ Tường Linh

Đỗ Tường Linh: Could you share a bit about the time when you first began making performance works? Back then you were studying at the Vietnam University of Fine Art...

Vừng ơi! Mở ra Sesame, open!

“Sesame, open!”—a phrase from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves —has always meant more than just opening a door. It’s about discovering something hidden, something precious. It was used as...

Trần Lương interviewed by Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy

Thanh-Mai Bui-Duy: Performance wasn’t your starting point, yet it plays an important role in your practice. How did that journey begin? Trần Lương: In the very beginning, getting into contemporary...